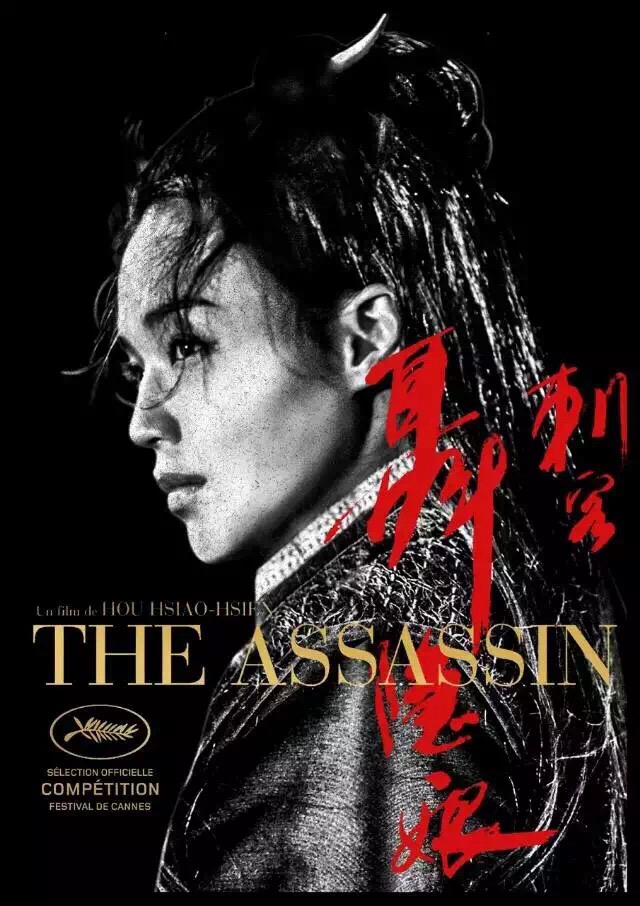

Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s “The Assassin” was originated from the classic “Legendary” created by Pei Xing lived in the Tang Dynasty. The language of the whole film is all written in ancient Classical Chinese (also known as “Literary Chinese”). Silent and beautiful images with artistic and recondite realms, which had kept the shifting long-shot cinematography that the director persists since his early works. Mark Lee Ping-Bing, holding a post as the cinematographer, shot the entire work with filmstrip (which is seldom used in today’s film industry, and normally replaced by digital technology). The narrative method was also adopted the conception of the Classical Chinese articles. The dialogue was compact but concise, the over description was superseded with the elegant landscape. This kind of traditional Chinese expression, which is at odds with the trend, can be found in the film history quite rarely.

Throughout Hou’s numerous films, it can be divided into three theme forms: Local Type (such as “A Time to Live, A Time to Die”, “Dust in the Wind” and “Goodbye South, Goodbye”), Nostalgia Type (such as “Flowers of Shanghai” and “The Assassin”) and Youth Type (such as “Millennium Mambo”). Hou Hsiao-Hsien made a film called “Three Times” to summarize his temporary film career, interestingly recounting three love stories happened in three different periods, which were represented the three forms mentioned above exactly. It is able to feel sensitively during the development of the director’s creation, that with the accumulation of time, that kind of sharp impulse which once can be found in the film “A City of Sadness”, becomes solid and profound gradually.

*The film criticism was written by Simplified Chinese at first (which is my mother tongue), then I translated into English for your reading convenience. And down there is the original version.

侯孝贤的《刺客聂隐娘》典出自唐人裴铏所撰《传奇》。全片通篇文言,映象静美,意境深邃,保持了导演一以贯之的长镜头移镜拍摄手法;李屏宾任摄影指导,用胶片拍摄而成。电影叙述手法也采用了古式文言概念,对白精简却显凝练,以清丽山水代替特写赘述。该异于潮流的传统中国式表达,在影史中甚为少见。

通观侯孝贤的众多电影,大致可分为三种题材类型:乡土(童年往事、恋恋风尘、南国再见)、怀旧(海上花、聂隐娘)与青春(千禧曼波)。《最好的时光》是他对自己电影生涯所作的一次总结,分别诉说了三段不同时代背景中的爱情故事。可以察觉,《悲情城市》中的那份冲动锐利,随着时间积淀为了深沉厚重。